What Did We Make and Why - The Problem Statement

This will be a brief, candid blog post discussing the thought process and origin of creating a new product. It will be a three part series starting with The Problem Statement, then Concepting/Ideation, and finishing with Design.

Introduction

A typical origin for a new product's life starts by observing some difficulty, pain point, or struggle and thinking there could be a way to make this easier. An alternate origin would be observing an existing product and thinking that it is lacking in some way and it could be made better, stronger, faster, etc. For the purposes of this blog we are going to focus on the original problem. So now that you have observed a problem in your day-to-day, which is a great first step, you would like to solve this pain point. It is easy and intuitive to jump to ideas for a ‘finished’ product that may provide the solution. NOT SO FAST THOUGH! Jumping to solutions is a surefire way to create a product that isn't as optimized as it could be.

Let’s explore how to more methodically address real-life problems (hint: it starts with defining the problems) and how to ultimately reach a successful product idea.

Observations

It is easy to notice something that you dislike and dismiss it as frustration, but it takes another skillset to observe a pain-point and form a solution to the problem causing the frustration. I try to do this in my life--I am constantly searching for the next soda pop pull-tab opener hidden in plain sight, waiting to be uncovered. However, all too often I find myself frustrated with something like traffic (which is arguably a much harder and more systemic problem to solve than opening an aluminum can). But, you did it, you observed something that bothered you and came to the conclusion that it can be solved, or at least improved.

Problems

Boy do we got ‘em! Understanding and defining problems is BY FAR THE MOST IMPORTANT PART of creating a product. Understanding and defining what problem(s) you are solving should drive all future decisions. It is logical, after observing a pain-point and thinking you can solve it, to jump to a finished product. But there are many, many steps between the observation and the finished product so it is extremely important to fully understand the problem that is being solved which is then driving the development of the product. The problem(s) should be the north star or guiding principle that steers the ship of development. This may sound like fluff (it’s not, I promise), but let’s do a quick thought experiment:

It’s the year 1959, you are at a picnic with some friends and you go to grab everyone soda out of the cooler (nice move) but you realize you forgot the can opener (tragic). For additional context, the soda can pull-tab has not been invented…yet. You are bothered by this annoyance and forced to find some other tool (maybe a rock) to open the soda. Soda inevitably goes everywhere and everyone leaves sticky.

Let's break down how solving for this problem might work:

Problem = Forgot can opener for soda

Observation = In order to open a can of soda you need an additional tool

Here is where the story could take two different paths when attempting to solve this pain point. Path one, you immediately jump to a finished product in your head--how about a necklace that is also a can opener? Sweet, we solved the problem, now if you wear this necklace you will always have a can opener and will be able to drink soda anywhere anytime! Clearly this is not the path history took, thankfully.

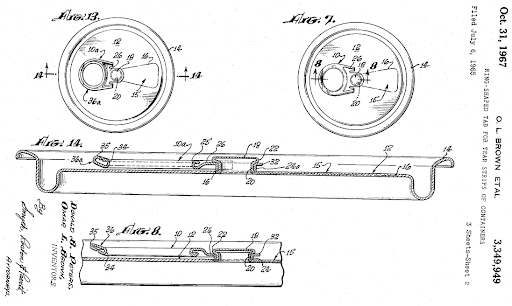

What about a different path? This happens to be the path Ermal C. Fraze took, who is the inventor of the pull-tab opener now ubiquitously found on aluminum cans (Patent #: 3,349,949, RING-SHAPED TAB FOR TEAR STRIPS OF CONTAINERS).

Obviously when we compare these two paths with perfect hindsight it is easy to see that, although both solve the problem, one may make you lots and lots of money and is impossible to forget, and one will solve the problem for a potential small group of interested individuals who also lack any amount fashion-sense.

The Problem Statement

The goal of this blog is to highlight the importance of fully understanding and describing the problem that is being solved when developing a product. Better understanding the fundamental problem will make development easier and will ultimately lead to a much better product--maybe you will come up with the next soda pull-tab opener and hopefully not a can-opener necklace. Before proceeding to solve a problem (with a brainstorming or ideation session), make sure you have a solid problem statement.

For soda can pull tabs, a half-baked problem statement would be “people forget their can-openers.” This statement will narrow our solution’s focus to something that makes sure a can-opener is always around. A much better one would be “soda cans require the consumer to use a can opener to dispense.” The latter problem statement might lead to a can-opener-necklace, but just as easily might lead us to rethink the fundamental need for a can-opener tool and if it can be avoided.

So, before you solve your problem, make sure you have well defined what it is from the most fundamental perspective and go from there.

Next step: ideation!

Interested in learning more about Boulder Engineering Studio? Let's chat!

Previous Blog Posts

Fatigue Part 1 |

Defining a Product |

|

|

.svg)